Executive Summary

The history and success of the Washington Redskins is important to the National Football League, fans of the team, and the heritage of American sports. Washington has won the Super Bowl three times in its storied history, and is one of the strongest brands in all of sports. The Redskins organization helps local and Native American groups through its strong foundations and charitable events, and supports environmental concerns through a solid program of environmentally friendly and ground-breaking resource management.

The great narrative of the Redskins’ success, however, is marred by the controversy over the name itself. Trademark case losses, announcers refusing to use the team’s name, and commentary from local politicians raises concerns from the public that, despite the organization’s great achievements, the only concern that matters is the name of the team and its potential for insensitivity.

Just in the last two weeks, the controversy over the name has erupted again through the satire of the popular Netflix series Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. The series spends several episodes making fun of the Redskins organization, the team name, and the employees of the organization directly. As the series has gained in popularity, several clips from the show have gone viral, reopening the issue of reputation with the public and potential sponsors.

Negative news has a deeper impact on the public and important stakeholders than positive news, and this proposal offers a change of direction centering on the narrative of the Redskins. NPR quoted a Washington Post poll reporting that 8 in 10 fans want to keep the team name, and those numbers support a change in narrative to convince the other 20% of the team’s value.

Instead of a small group controlling a narrative of insensitivity, this proposal strengthens the message that the Washington Redskins are an important part of the local community and a fervent supporter of Native Americans. Highlighting the work of the various Redskins charities, and an emphasis on the storied history of the team and the nation, will push the controversial topic out of the minds of stakeholders. The reputation of the Redskins organization will move forward, moving from name vilification to respect for all that the organization does for others.

Working with Native American groups, the local Washington, Virginia, and Maryland communities, and media groups are the vital first step in a new narrative strategy. Opening up a dialogue with affected communities presents the opportunity to move the narrative towards reconciliation, and a mutual understanding of the needs of all participants. Along with continued dialogue about the name, a focus on consistent charitable contributions from the Redskins organization will be used to foster goodwill. The intent is for the other groups to share in the advocacy of the organization’s reputation, to change opposition into a positive view of the Redskins by all stakeholders.

Along with meetings and open discussions with other groups, implementing a new narrative involves social and news media campaigns and shared knowledge throughout the organization. All members of the Redskins staff will understand and promote the new narrative, and a combination of social media and advertising will continually promote the ethics and reputation of the organization. Interviews, articles, and broadcast features, made in collaboration with the organization and various media outlets, will push the narrative both locally and nationally. Highlighting these media tie-ins will be a focus on the continued communications between communities, Native American groups, fans, and stakeholders within the Redskins family.

But all of these changes are just empty talk without a way to measure the impact of the new narrative. The final important piece of the proposal is evaluating how these actions change the perceived reputation of the Washington Redskins. Brand measurement and equity will be followed from its current level, through implementation of the new narrative, and at least one full year afterwards. An examination of news media reports, response from local communities and Native American groups, and feedback from all stakeholders will be measured and compared in an effort to satisfy the intent of increasing the reputation of the organization.

This proposal changes the narrative of the Washington Redskins, from the negative connotation of the name to the strength of the Redskins’ dedication to the community. The reputation of the Redskins will no longer hinge on the views of a smaller group concerned about a name. The new narrative will increase the strength of the Redskins reputation as a vital player in the community, a strong advocate for Native Americans, and a leader in the sport.

Introduction and Issue Management

The current narrative of the Washington Redskins, about the perception of the organization’s troubled name, is being spun by a small group with the potential for a larger impact. Some Native American groups and media discussions have portrayed the Redskins under a veil of racism and disrespect based on the perception of the Redskins moniker. The potential impact on reputation, finances, and the continued well-being of the organization are at stake.

Taking control of the narrative is vital to moving the organization past the naming issue, and into a fruitful relationship with the sport, community groups, and the general public. Highlighting the storied history of the organization, coupled with its tireless charitable and community-oriented activities, will shift the negative portrayal of the Washington Redskins into a more positive light.

Improving the reputation of the Washington Redskins requires seven stages to accomplish. Starting with a look at the current environment of the Redskins and the community around them, the proposal will identify key elements to focus on. Prioritizing and analyzing these issues will lead to decisions on the strategies that will be used to help the organization’s reputation. Implementing a strategic plan, and evaluating how effective it is over time, will allow the Redskins to measure and restore their reputation.

Stage 1: Monitoring the Redskins Business Environment

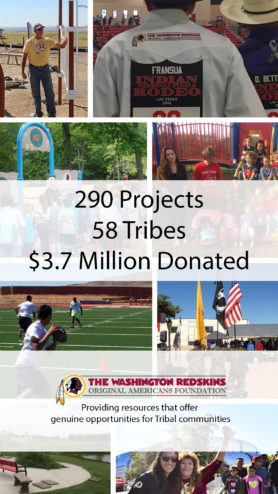

Sample advertisement promoting charity work

The Washington Redskins organization is listed as one of the most successful NFL teams, and provides support to local and Native American communities through the Washington Redskins Original Americans Foundation (WROAF) and local charitable events. As a three-time winner of the NFL Super Bowl, and a reported net organizational worth of over $2.95 billion (Forbes, n.d.), the Washington Redskins are a clear success on the field and in the financial arena. The WROAF provides numerous support activities for Native American tribes, including education and youth support, health and community services, and economic development (WROAF. 2016). The financial and charitable successes of the organization offers a clear representation of the communities, fans, and people that it serves.

The history of the organization is important to the ways in which the Redskins portray themselves to stakeholders, including the much-discussed name. The Redskins moniker, according to team legend, honors one of the team’s first coaches, William “Lone Star” Dietz, who not only identified as Native American but also brought a number of Native American players to the team (Gandhi, 2013). Historically, the term “redskin” was initially used by Native Americans to identify themselves as different from Europeans in the 17th and 18th centuries (Gandhi, 2013). In the 19th century, popular books by James Fenimore Cooper like The Pioneers were sympathetic to Native Americans, and used the redskin name to identify them. Even as late as 1929, the successful film Redskin respectfully used the name to identify the main character.

But as the 19th century gave way to the 20th century, despite the anomaly of the film Redskin, the term took on a harsh, racist meaning. Stereotypical displays of Native Americans as primitive savages, always pushing for bloodier and bloodier conflicts, reigned in the cultural eye, and it was not until the 1960’s that the term fell out of favor (Gandhi, 2013). In light of the controversial meaning of the term in modern culture, many have called for the Redskins to change their team name to something more politically correct.

Political debate on the name has come from both local and national leaders. The mayor of Washington D.C., members of Congress, the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, and many former players have stated that the name should change (Gandhi, 2013). Several gubernatorial candidates in Virginia were asked about the name, with some being fully against it and others feeling that the controversy was “much to do about political correctness” (Johnson, 2017). The debate over the name is in the public consciousness, which may provide both opportunity and need to change the narrative.

Economically, the Redskins organization is one of the strongest in the NFL. Between game day attendance, team value, merchandise and other contracts, and both direct and shared sponsorships, the organization is valued at over $2.95 billion (Forbes, n.d.). With the average value of NFL television broadcast contracts being between $1.9 billion to $3 billion split between teams, the Redskins have a stellar financial outlook (Schoettle, 2014). While the team is a financial success, there is a concern that if the stakeholders lash out, sponsorships and other financial support could be lost due to reputation.

The social media response to the name could harm the reputation of the organization, and with the speed and viral nature of the internet that could be a growing issue. A poll from the Washington Post showed that 8 out of 10 fans wanted to keep the Redskins name, but less than half felt they would use it outside of a football discussion due to its inappropriate meaning (Gandhi, 2013). Examination of the commentary left on the Washington Redskins Facebook page shows little concern for the name, and mostly discussion of the current players and team dynamics.

Legally, the Redskins have faced an uphill battle with the trademarks protecting the organization’s interests and brands. Many argue that any use of a Native American name, term, or symbol is negatively against the Native American culture, and continues the harsh stereotypes from the early 20th century (Bollinger, 2016). Based on a similar interpretation, the United States Patent and Trademark Office Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) cancelled 6 trademarks owned by the Redskins in 2013, considering those trademarks to be disparaging to Native American culture (Cannata, 2014). With the case possibly entering the U.S. Supreme Court in 2017, not only will the topic emerge again but the value of adjusting the narrative is paramount to success both legally and publicly.

Ecologically, the United States is entering a difficult time in negotiations dealing with climate change, and the Redskins dedication to renewable energy is a highlight of the current business environment. As the U.S. government backs away from the Paris climate agreement, other organizations can step up their green efforts. With the Redskins being awarded for their work with renewable energy initiatives by the local Prince George’s County Chamber of Commerce, there exists a strong opportunity for the Redskins to acquire great social and news media coverage (Tinsman, 2012). That business and environmental stance is a light ready to be used in a time of uncertainty on climate change and ecological support.

Stage 2: Identifying the Scope of the Issues

Discussion and concern over the use of Native American terms and mascots has been ongoing for decades. Native American groups previously tried to cancel the Redskins’ trademarks in 1999, offering evidence of problems with the name as far back as earlier trademarks in 1967 and 1990 (Cannata, 2014). In 2005, the NCAA created policies that would eliminate the use of Native American names and mascots throughout its system, inferring that American culture had reached a point where those terms were no longer acceptable (Bollinger, 2016). It is a discussion and concern that is widely open in the public realm, a conversation that threatens any team using a Native American term as a name.

Some sports announcers have started to avoid using the Redskins name during major broadcasts, instead referring only to their location. Figure 1 below shows that mentions of the Redskins name was down 27% between 2013 and 2014, averaging only 81 mentions per game in 2014 versus 111 mentions per game in 2013 (Burke, 2014). In 2014, several popular broadcast television announcers said that they would no longer use the term at all, instead referring to the team as simply “Washington” when required (Blaze, 2014). That unwillingness to use the term in such a public arena sends a strong message to viewers that the name is an issue, and the organization faces a potentially strong public backlash when even their favorite broadcasters will not use the name.

Figure 1: Burke (2014). “Redskins” mentions down 27% on NFL game broadcasts in 2014

If fans find that their favorite broadcasters do not want to use the name, they may also not want to be associated with the name. That could lead to the team losing its audience, or even being offended by the controversial name. Fans may choose not to support team sponsors, react to advertisers unfavorably, or decide not to purchase merchandise. Considering, however, that 8 out of 10 fans in the Washington Post poll would still not want a name change, the impact may be less on fans and more on others (Gandhi, 2013). Team sports fans often feel a part of the group, and are hardier when it comes to a team scandal so as not to lose that sense of belonging (Chien et al., 2016). While sponsors and media could abandon the team due to the name, which would mean millions of dollars in lost revenue, fans would stay with the organization where others might not come into the fold. It is an issue affecting the future of the team, where new fans might not bother with a conflicted organization.

Stage 3: Prioritizing

With the U.S. Supreme Court possibly reviewing the trademark case this year, it is important to act on reputation issues before that time. This proposal offers a strategic plan to change the narrative, but it takes time to work through issues that have a long lifecycle like the controversial name. The time to act is now, before the controversy can create a larger narrative that takes away from the upcoming football season. A distraction of that magnitude can remove sponsors, merchandise purchases, and media viewership during the premium fall time frame. The impact of the controversy includes future revenue loss, further damage to organizational reputation, and a much more difficult stance to take as time goes on.

Along with the upcoming Supreme Court review, popular culture has also started to take notice of the controversy. A segment on the television series The Daily Show featured Redskins fans who were asked to say the name to Native Americans in the same room, and the clip went viral (Bollinger, 2015). In the last two weeks, the Netflix series Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt has had several scenes of its latest season go viral, and several of the episodes satirize the Washington Redskins, the controversy, and even the employees involved (Carlock et al., 2017). The effect of popular series satirizing the controversy is one of advocacy by thousands on the web, and without a better narrative more and more people will jump on the bandwagon against the Redskins organization.

Stage 4: Analysis of the Issues

Maintaining a strong reputation involves vigorous communication, an understanding of the impact of the issue, and methods to repair organizational image. The controversy over the name is a conflict against the Redskins organization, and much like an attack condition the organization needs to be able to defend itself and improve any reputational damage that had occurred.

Public perception of the organization’s reputation naturally rises and falls to a certain degree based on team performance during a season, but the name issue is a concern that stays with the Redskins both on and off the field. The reputation of the brand falls harder and further when negative news is causing controversy, and negativity pulls greater weight than positive news (Wang, 2008). Stakeholders may find that negative information is more important to evaluate the organization with, a sense that it is more useful than positive information (Wang, 2008). In that sense, the continued controversy is slowly dragging down casual fans, and if the pressure becomes too great may begin to impact more dedicated fans as well.

If fans stop supporting the team, the effect on the organization will become greater as time goes on. Fans abandoning the team over the name will cause a loss of revenue in ticket sales, lost taxes for local communities, and possibly denial of continued contracts, sponsorships, and new stadiums. With football being an international phenomenon, the immediacy of sports news and viral social media updates, and a greater sense of advocacy by online fans, keeping a good reputation and repairing it in times of distress is of massive importance (Brown et al., 2016). Repairing the waning image of the Redskins, changing the narrative from one of insolence to one of compassion, is vital to lessening the impacts of allowing the controversy to continue.

Allowing the controversy to continue affects a number of different stakeholders, in different ways. The types of stakeholders in a sports organization are vast, even nationwide, and the impact of a reputation failure can cause enormous distress throughout. Figure 2 lists a number of stakeholders and how they might be impacted by the controversy.

|

Stakeholder |

Effects |

|---|---|

|

Employees, team and management, support staff |

Reputation; Revenue loss leading to job insecurity, loss of wages, lower benefits; Legal ramifications |

|

Local community |

Loss of tax base, travel and tourism revenue, population |

|

Other NFL teams and organizations |

Reputation; Loss of shared revenue and advertising base; |

|

Native American groups |

Loss of charitable donations; Gain in changing perceived racist name if changed |

|

Media outlets and contracted networks |

Loss of advertising partner and television/promotional revenue; Loss of sports and other journalists; |

|

Redskins and NFL fans |

Loss of group identity for individual fans; Financial loss from previous merchandise and ticket purchases |

Stage 5: Choosing the Right Strategy

To repair the Redskins image and increase organizational reputation, there are several possible strategies that can be used. Keeping fans loyal is important to any strategy, as is gaining new fans, and the response to the controversy needs to avoid using apologies that would infer fault (Brown et al., 2016). Instead, by using the history of the organization and the term, and being honest in all communications, stakeholders will be more trusting and more open than an apology would provide (Brown et al., 2016). Honest and open communication allows for the implementation of the best strategy to use moving forward.

Without open communication, both sides of the discussion could fall into problematic tactics meant to damage the other party. Those against the name will surely go on the attack through social media and news organizations, proclaiming injustice and irresponsibility in keeping the name intact (Coombs & Holladay, 2015). Protests at the stadium during game days, at Redskins offices on off-days, and at away games, will be used to garner support for changing the name. Picketing, social media postings, local pamphlets, and other promulgation agitation techniques will be used by those seeking to change the name, in an effort to gain as much public support as possible (Coombs & Holladay, 2015). On the Redskins side of the conflict, the organization might choose repression to prevent such actions, including suing participants and affiliated groups, and making it more difficult for protesters by closing areas and increasing security (Coombs & Holladay, 2015). Suppression of the message may work in the short term, but both sides face a harsh backlash with continued conflict going nowhere.

While suppression is an identified strategy, there are other strategies to put into play. These choices include trying to persuade the other party that they are wrong, making some changes to goals or problems, or fully capitulating to all demands (Coombs & Holladay, 2015). The differences come down to the type of strategy that the organization wants to make. The best choice for the Redskins would be to use accommodative strategies in an effort to work with the other side, not apologizing for the name but working through responsibility and action (Jeong, 2015). Using a differentiation strategy, the Redskins can alter how people see the organization and give accusers a new perspective (Utsler & Epp, 2013). Working with Native American groups directly can change the sentiment around the name into a positive working relationship. In explaining how the organization provides financial support to tribes and communities, the Redskins can transcend the discussion, from a bully team stealing a name to an organization spending its time and money to help others who need it most (Utsler & Epp, 2013). The strategy of open communication, changing the narrative, and transformation helps both sides to meet in the middle, and increases the strength of the Redskins organization.

Sample advertisement promoting history

Changing the narrative to increase reputation starts with a close relationship between the Redskins and Native American groups. Working with Native American groups in a very public, open discussion, will allow the free range of feelings about the name to happen. Finding out how all of the Native American groups truly feel about the name will satisfy the sense of whether or not a future name change would be relevant. Discussion about the name should happen on a local and national level as well, with open communications between the NFL, other teams, area government, and fans across the nation. To start, private discussions between Redskins management, Native American groups, and NFL officials could start the process. As the ground rules are laid, top management can offer media interviews while negotiations with all organizations become more public. With continued dialogue about the name, a focus on consistent charitable contributions, and attention to local communities the Redskins can foster goodwill.

Stage 6: Implementing the Strategy

Implementing the strategy to change the narrative of the Redskins begins with the employees of the organization. Each staff member is a potential custodian of the new narrative, and each employee must understand how the narrative is turning away from the name and towards history and charity. As the plan is being implemented, training begins in early July for upper management, in order to educate the entire organization long before the first game on August 10. In the second week of July, upper management in turn relays the message to each of their department heads, followed the next two weeks by departments filling out the rest of the information.

During July and August, upper management and team personnel will set up or attend meetings with NFL officials, team owners, and managers, along with Native American groups from across the United States. The meetings are designed to inform each group of the narrative, and get feedback from all groups on how to proceed. Once initial meetings are complete, representatives from all sides can meet prior to the beginning of the season to coordinate social and news media contact.

As August proceeds, the Redskins can build confidence and reputation through interviews, articles, and broadcasts with the news media. Social responsibility in an organization can be received as being more credible by the public based on how they get their information, and the strong work with the news media can help the Redskins with the credibility of the new narrative (Wang, 2008). Using local and national news media gathers attention for the Redskins and, when included with the open lines of communication to the Native American groups, offers an opportunity to advance the message broadly.

At the same time as the organization is working through the news media, the Redskins social media accounts can use a constant campaign of information to spread the new narrative. Using visuals promoting the new narrative, including photos and videos, enhances how much people will remember from the campaign (Alhaddad, 2015). Sports teams can effectively use social media to influence the personality of the brand, and increase the brand’s rating through control of that image (Walsh et al., 2013). A promotional social media campaign of images and videos will be created to tell the narrative of the history and generosity of the Redskins organization. The strength of the Redskins’ social media will drive brand equity even further, and the narrative will be in the control of the organization.

Stage 7: Evaluating the Response

All of these changes are just empty talk without measuring the impact that the new narrative has on the reputation of the Washington Redskins. Evaluating how these actions change the perceived reputation includes brand measurement and equity, from its current level, through implementation of the new narrative, and at least one full year afterwards. Examining news media reports, social media metrics, local community and Native American response, and feedback from important stakeholders are all vital to satisfying the intent of increasing the reputation of the organization.

Increases and decreases of brand equity will be tracked over time through several measurement companies, each using different methods to rank brands. Increasing brand equity is a solid measurement for the impact of the new narrative, and combining the views of multiple methods gives a strong idea of how the brand is doing over time. Figure 3 features the different brand measuring companies, and how they measure brand equity.

|

Company |

Methods |

|---|---|

|

Interbrand |

Financial performance, role of the brand vs. unbranded items, brand strength for future earnings |

|

Millward Brown |

WPP BrandZ database records of consumer brand evaluations; Branded earnings, brand contribution, brand growth potential |

|

Young & Rubicam |

Brand Asset Valuator; Uniqueness of brand, relevance/vitality, esteem, knowledge or degree brand is in everyday life |

|

Harris Interactive |

EquiTrend; equity (familiarity, quality, and consideration), connection, commitment, energy |

|

Corebrand |

Brand Power; overall reputation, perception of management, investment potential |

Figure 3: Measuring corporate brands (Roper & Fill, 2012, p. 166-170)

Each social media network provides analytics for tracking responses, interests, and various types of traffic data to show the impact of the narrative both at the moment and over time. Every time a post occurs on Facebook, for example, analytics will show how many times it was ‘liked”, viewed, shared with others, and what level of engagement each of the user’s friends had with it. Since the Redskins use Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram primarily, each post will be tracked through each service’s media options, along with Google Analytics to follow traffic on the Redskins website. Reports on the campaign and the effect of the new narrative will be made daily for the first three weeks, weekly for the next two months, and monthly for the remainder of one year.

News media coverage, including newspapers, magazines, television and radio broadcasts, and websites will be tracked for discussion or mention of the Redskins. News alerts will be set up through sites like Google News, Bing, and Yahoo, as well as services like Newstrapper, Facebook Signal, and Storytracker. Comments and mentions will be tracked through similar services, by connecting with comment systems such as Disqus, and through targeted keyword searches. Reports will be made on the same schedule as social media reporting.

The Redskins website, email newsletters, and social media pages will also be used to offer surveys, polls, and other response gathering techniques to gauge how the organization’s message is working. Polls and surveys will be timed to come out before or after a major part of the campaign has begun, to track data and information from multiple angles.

Throughout the campaign, direct feedback will be asked for from Native American groups, local communities and governments, other NFL teams and officials, and media organizations. Each effort will be either in person, over the phone, or through written efforts, to keep the lines of communication and feedback open throughout the campaign.

Conclusion

The current narrative of the organization portrays the Redskins under a veil of racism and disrespect, and the time has come to take control of the narrative. With the potential impact on reputation, finances, and the continued well-being of the organization at stake, taking control of the narrative is vital to moving the organization past the naming issue. Highlighting the tireless charitable and community-oriented activities of the Redskins and their storied history will shift the negative portrayal of the Washington Redskins into a more positive light.

References

- Alhaddad, A. A. (2015). The effect of advertising awareness on brand equity in social media. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning, 5(2), 73-84. doi:http://dx.doi.org.csuglobal.idm.oclc.org/10.17706/ijeeee.2015.5.2.73-84

- Blaze. (Aug. 18, 2014). Two major NFL announcers say they won’t use term ‘redskins’ on the air. Retrieved from http://www.theblaze.com/news/2014/08/18/two-major-nfl-announcers-say-they-wont-use-term-redskins-on-the-air/

- Bollinger, S. J. (2016). Between a tomahawk and a hard place: Indian mascots and the NCAA. Brigham Young University Education & Law Journal, (1), 73.

- Brown, K. A., Anderson, M. L., & Dickhaus, J. (2016). The impact of the image repair process on athlete-endorsement effectiveness. Journal of Sports Media, 11(1), 25-48.

- Burke, T. (Dec. 30, 2014). “Redskins” mentions down 27% on NFL game broadcasts in 2014. Retrieved from http://deadspin.com/redskins-mentions-down-27-on-nfl-game-broadcasts-in-1676147358

- Cannata, M. C. (2014). Trademark trial and appeal board cancels six trademark registrations owned by the washington redskins. Intellectual Property & Technology Law Journal, 26(10), 25-27.

- Carlock, R. (Executive Producer), Fey, T. (Executive Producer), Miner, D. (Executive Producer), & Richmond, J. (Executive Producer) (2017). Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt [Television Series]. United States: Netflix, Inc.

- Chien, P. M., Kelly, S. J., & Weeks, C. S. (2016). Sport scandal and sponsorship decisions: Team identification matters. Journal Of Sport Management, 30(5), 490-505. doi:10.1123/jsm.2015-0327

- Coombs, T., & Holladay, S. (2015). CSR as crisis risk: Expanding how we conceptualize the relationship. Corporate Communications, 20(2), 144-162.

- Forbes. (n.d.). Sports money: 2016 team valuations. Forbes Online. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/teams/washington-redskins/

- Gandhi, L. (Sep. 9, 2013). Are you ready for some controversy? The history of ‘redskin’. NPR.org. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/ 2013/09/09/220654611/are-you-ready-for-some-controversy-the-history-of-redskin

- Jeong, J. (2015). Enhancing organizational survivability in a crisis: Perceived organizational crisis responsibility, stance, and strategy. Sustainability, 7(9), 11532-11545. doi:http://dx.doi.org.csuglobal.idm.oclc.org/10.3390/su70911532

- Johnson, R. (Apr. 18, 2017). Will Va.’s next governor roll out the welcome mat for the Redskins? WTOP.com. Retrieved from http://wtop.com/virginia/2017/04/virginia-governor-candidates-redskins/

- Roper, S., & Fill, C. (2012). Corporate reputation: brand and communication. Harlow, England: Pearson.

- Schoettle, A. (2014). Colts cash in. Indianapolis Business Journal, 35(23), 3.

- Tinsman, B. (June 5, 2012). Redskins recognized for green initiatives. Retrieved from http://www.redskins.com/news-and-events/article-1/Redskins-Recognized-For-Green-Initiatives/2f8ea25b-ba35-44a3-8aaa-09a0bdd06b59

- Utsler, M., & Epp, S. (2013). Image repair through TV: The strategies of McGwire, Rodriguez and Bonds. Journal of Sports Media, 8(1), 139-161.

- Walsh, P., Clavio, G., Lovell, M. D., & Blaszka, M. (2013). Differences in event brand personality between social media users and non-users. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 22(4), 214-223.

- Wang, A. (2008). Dimensions of corporate social responsibility and advertising practice. Corporate Reputation Review, 11(2), 155-168. doi:http://dx.doi.org.csuglobal.idm.oclc.org/10.1057/crr.2008.15

- WROAF. (2016). Washington Redskins original americans foundation hosts 150 guests at Redskins Cardinals game. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonredskinsoriginalamericansfoundation.org/whats-happening/2016/12/washington-redskins-original-americans-foundation-hosts-tailgate-redskins-cardinals-game/